2017, New Internationalist

Written by Brad Evan and Sean Michael Wilson

Art by Inko, Carl Thompson, Robert Brown, Chris Mackenzie, Michuru Morikawa, Yen Quach

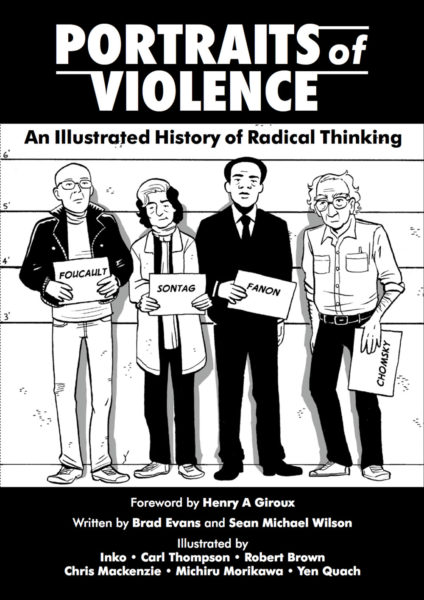

The journey from pitch to publishing date is always a far longer one than most readers will ever appreciate. That Portraits of Violence: An Illustrated History of Radical Thinking releases this month, then, is probably as much fortune as it is forethought for creators Brad Evans and Sean Michael Wilson. However, for the rest of us watching events unfold in a post-Brexit and pre-Trump landscape with jaws agape, this collection of visual essays is a stark and pertinent reminder of the importance of critical thinking, and the pursuit of truth and reason.

Evans (academic) and Wilson (comic book writer) gather some of the past century’s most celebrated minds on the subject of violence, covering such critical thinkers as Susan Sontag, Noam Chomsky, Frantz Fanon, Judith Butler, Michel Foucault and Hannah Arendt in just 10-pages each.

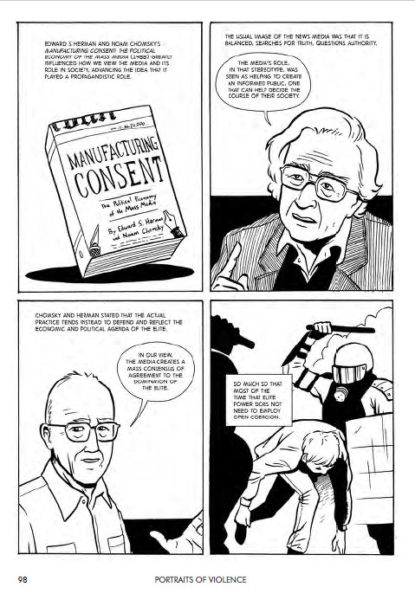

I’ve previously referred to comic books as a sort of shorthand when it comes to telling a story or expressing an idea. The medium is able to do wonderful things with its own version of what filmmakers know as the The Kuleshov effect, with the reader’s imagination filling in the blanks between sequential images. The ten artists involved all deliver a different take on Evan and Wilson’s scripts, with the most successful attempts such as Carl Thompson’s visualisation of Manufacturing Consent* offering a distilled version of Chomsky’s seminal and never more significant work that crams so much into so little space, stripping the source material of its words but not its impact. Arendt’s term “the banality of evil” is also awarded considerable substance and viscera by Chris Mackenzie.

One of the approaches to the book I particularly enjoyed is that, in condensing these thinkers and their philosophies into the comic book medium, Evans and Wilson maintain their own distinct voice. This lends Portraits of Violence a level of consistency in spite of its disparate sources and art styles, allowing the book to work as an overview of radical thinking and non-violent theory from the 21st century. The juxtaposition between narration and quotes via speech bubbles also avoids a certain didacticism that may have initially deterred fresh young minds from reading the source material.

While the different segments all tackle violence from a separate angle and historical context, if there’s a single strong underlying message running throughout Portraits of Violence, it’s one of pedagogical change; of the need to educate future generations to view the world through a critical lens, and to forever question the narrative woven by the media. Or, as Evans puts in his chapter on Paulo Friere and Henry A. Giroux (who also provides the foreword) to prevent “schools churning out drone-like, debt-ridden employees for the market, imbued with authoritarian values, inured to violence bother and home and abroad.”

Portraits of Violence is an extremely timely book, then, and one adapted with both reverence and soul. While I am familiar with most of the philosophers featured and would love to tell you to experience the original texts first, the only featured work I’ve read in its entirety is Manufactured Consent. Yes, I’ve shamed myself. What would people like me do without comics such as this?

Portraits of Violence is out 19th January, from New Internationalist. You can read two extracts from the book, which focus on Hanna Arendt’s ‘The Banality of Evil’ and Frantz Fanon’s ‘The Wretched of the Earth’, at www.historiesofviolence.com.

Leave a Reply