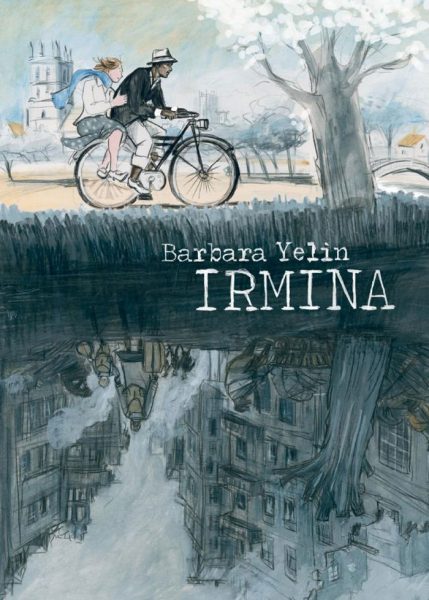

SelfMadeHero, 2016

Written and illustrated by Barbara Yelin

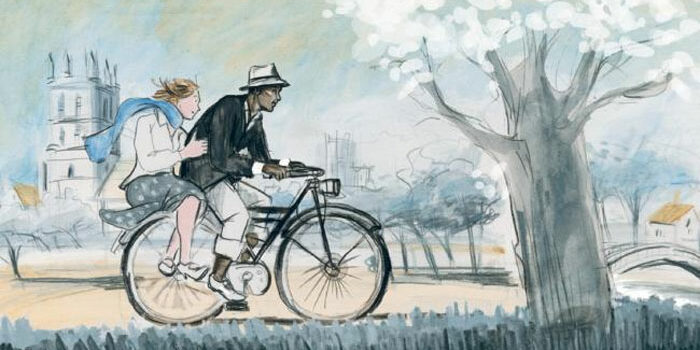

Munich-born comic artist Barbara Yelin must have felt as though she’d been blessed by the gods of creativity when she serendipitously discovered a box containing her grandmother’s diaries and letters. They told of a young German woman who had studied in London during the early 1930s and fallen in love with Howard Green, one of Oxford’s first black students, discovering herself and her independence in the process.

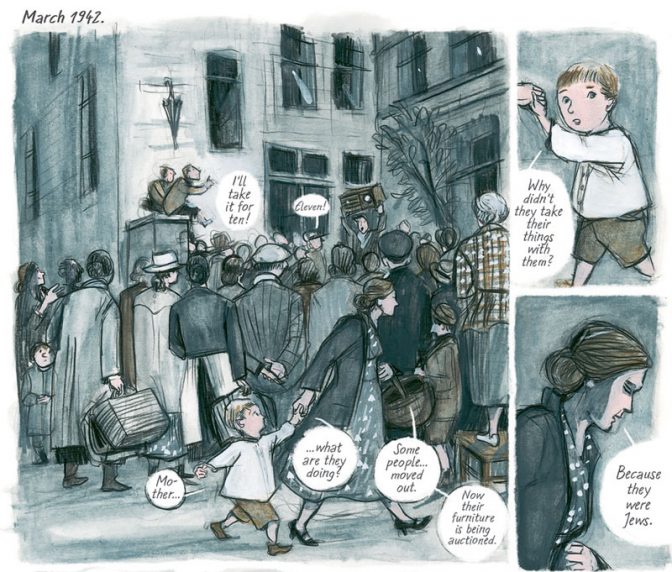

But when financial woes required Irmina to retreat home during the transition of the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, her promise to return to Howard was burdened by circumstances beyond her control. Irmina’s diary gave Yelin insight into a seemingly strong-willed woman who, against the principals she’d defined during her time in London, learned to look away from the cruelty inflicted upon her Jewish compatriots, eventually tolerating the Nazi regime in order to survive and protect her child.

A fascinating premise, then, and the sort of thought-provoking material SelfMadeHero has earned a fine reputation for publishing. As the dualistic cover suggests, much like Roberto Benigni’s unfairly maligned Life is Beautiful, Irmina’s narrative is driven by several abrupt changes in tone. The London-set sweet-natured tale of love and self-discovery (albeit one with a murky cloud lingering overhead) becomes a dreamlike memory as Irmina returns to a grey Berlin draped in red and emblazoned with Nazi insignias.

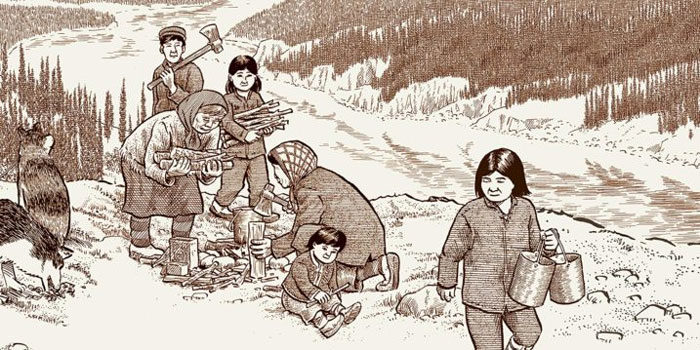

Barbara Yelin, who won the prestigious Bavarian Art Award for Literature for this effort, renders 30s London and Berlin with a confident sketchiness, one that is occasionally beautiful in its delicateness and at other times leaves much to the reader’s imagination. Like the best artists, her work appears effortless, but its attention to visual narrative and consistency tell of an immense labour of love.

Again, it’s a beautiful book, but Irmina is driven by Yelin’s masterful script, which unremittingly drags its central character’s happiness just a tiny bit further from reach. Irmina’s initial feelings towards the political upheaval in her home country are largely left a mystery to the reader. Like most of us, she simply wants to better her life, build a career and secure some semblance of happiness. As Dr Alexander Korb writes in the afterword: “people experience the commotions of history first and foremost through their everyday lives, so that personal watersheds like first love, choosing a profession, the birth of a child or moving house can be of greater biographical significance than historical events.”

Irmina’s unique depiction of a liberal working woman’s perspective on the Volksgemeinschaft through to the Second World War, then, ultimately becomes a broader examination of the human condition during conflict and atrocity. The quietly devastating final act, which takes us to a comparatively alien Stuttgard of 1983 and eventually sunny Barbados, reduced me to tears. I can’t recall another graphic novel that has achieved this.

Anyone who takes the comic medium seriously should read Irmina as soon as they possibly can. Much like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, I can see it becoming a classic that fans of the form and scholars alike will return to time and again.

Leave a Reply