1994

Adapted by David Mazzucchelli and Paul Karasik from the novella by Paul Auster

Widowed poet Daniel Quinn lives in isolation, writing noirish detective fiction under the pseudonym William Wilson. When he receives a phone call from someone mistaking him for real life detective Paul Auster – yes, the author of the novel from which this graphic novel is taken verbatim – he assumes the guise of in order to solve the case of Peter Stillman. Peter walks, talks and thinks in a manner entirely alien to the rest of his species; for nine years he was kept confined in absolute darkness by his father of the same name; an insane Religious philosopher who believed that depriving his son of language would allow him to learn the word of God.

As Quinn’s passage takes him to Auster himself – not the detective for Quinn he was mistaken, but the author of the book who just happens to have the same name – City of Glass’s detective trappings dissolve into a surreal tale of identity and reality, and the madness that inflicts anyone who is willing to gaze long enough into the world around them for answers.

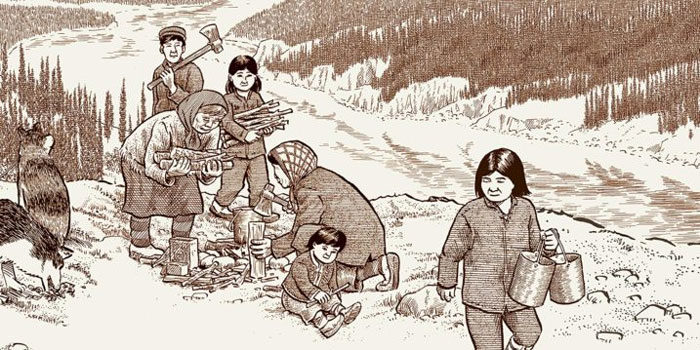

Muzzucchelli and Karasik’s adaptation is perhaps the sole example of a book to comic translation that rivals, if not transcends, its source material. I don’t know if there is a particular term to describe how one panel flows to the next, but City of Glass “flows” beautifully. In one scene, as the narrator describes how Quinn’s regular walks through New York stripped him of his individual identity, an abstract cityscape unravels into a maze, which then shrinks into a fingerprint upon the window by Quinn’s writing desk. It’s engrossing, almost rhythmical stuff, and the adherence to a nine panel layout makes the book a fittingly claustrophobic read.

What Auster’s original novel did so well was use the recognisable conventions of the detective novel without following them. His artfully existential plot, in which the detective finds no answers because there are none to be found, has undoubtedly pissed off as many readers as it has beguiled. I should know, as I was one of them when I read Auster’s New York Trilogy several years ago. It was only on reading City of Glass a second time, my expectations no more, that I was able to appreciate the book for what it is.

City of Glass formed the first part of Auster’s The New York Trilogy, in which each part was connected but no dependent on one another. Though the novellas were perfectly enjoyable individually, I do feel that an extra layer of conspiracy has been lost in excluding ‘Ghosts’ and ‘The Locked Room’.

But then City of Glass was always intended to be one piece short of a puzzle. If you’re the kind of reader who needs to know the answer to a riddle, then this might not be the book for you. As Daniel Quinn learns the hard way in Auster’s tale, if you look for answers too intently it’s likely to drive you insane.

8/10

Leave a Reply